What Does Under a Babys Tounge Look Like

| Natural language | |

|---|---|

The human being tongue | |

| Details | |

| Forerunner | pharyngeal arches, lateral lingual swelling, tuberculum impar[one] |

| Organisation | Comestible tract, gustatory system |

| Artery | lingual, tonsillar co-operative, ascending pharyngeal |

| Vein | lingual |

| Nervus | Sensory Inductive two-thirds: Lingual (sensation) and chorda tympani (taste) Posterior one-third: Glossopharyngeal (IX) Motor Hypoglossal (XII), except palatoglossus muscle supplied by the pharyngeal plexus via vagus (X) |

| Lymph | Deep cervical, submandibular, submental |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | lingua |

| MeSH | D014059 |

| TA98 | A05.ane.04.001 |

| TA2 | 2820 |

| FMA | 54640 |

| Anatomical terminology [edit on Wikidata] | |

The natural language is a muscular organ in the oral cavity of a typical tetrapod. It manipulates food for mastication and swallowing as office of the digestive process, and is the chief organ of taste. The natural language's upper surface (back) is covered by sense of taste buds housed in numerous lingual papillae. It is sensitive and kept moist by saliva and is richly supplied with nerves and claret vessels. The natural language too serves every bit a natural means of cleaning the teeth.[two] A major function of the natural language is the enabling of spoken language in humans and vocalization in other animals.

The man tongue is divided into two parts, an oral function at the front and a pharyngeal role at the back. The left and correct sides are as well separated along most of its length past a vertical section of fibrous tissue (the lingual septum) that results in a groove, the median sulcus, on the natural language's surface.

In that location are two groups of muscles of the natural language. The four intrinsic muscles change the shape of the tongue and are not attached to bone. The four paired extrinsic muscles alter the position of the tongue and are anchored to os.

Etymology [edit]

The word tongue derives from the Sometime English tunge, which comes from Proto-Germanic *tungōn.[3] It has cognates in other Germanic languages—for case tonge in West Frisian, tong in Dutch and Afrikaans, Zunge in German, tunge in Danish and Norwegian, and tunga in Icelandic, Faroese and Swedish. The ue ending of the word seems to be a fourteenth-century attempt to show "proper pronunciation", but it is "neither etymological nor phonetic".[3] Some used the spelling tunge and tonge as late as the sixteenth century.

In humans [edit]

Construction [edit]

The underside of a homo tongue, showing its rich blood supply.

The tongue is a muscular hydrostat that forms function of the floor of the rima oris. The left and right sides of the tongue are separated by a vertical section of gristly tissue known every bit the lingual septum. This segmentation is along the length of the tongue save for the very back of the pharyngeal part and is visible as a groove called the median sulcus. The human natural language is divided into anterior and posterior parts by the terminal sulcus which is a Five-shaped groove. The apex of the concluding sulcus is marked by a blind foramen, the foramen cecum, which is a remnant of the median thyroid diverticulum in early on embryonic evolution. The inductive oral function is the visible part situated at the front and makes up roughly ii-thirds the length of the natural language. The posterior pharyngeal part is the part closest to the pharynx, roughly one-third of its length. These parts differ in terms of their embryological development and nerve supply.

The inductive tongue is, at its apex, sparse and narrow. It is directed forward confronting the lingual surfaces of the lower incisor teeth. The posterior part is, at its root, directed astern, and continued with the hyoid bone by the hyoglossi and genioglossi muscles and the hyoglossal membrane, with the epiglottis by three glossoepiglottic folds of mucous membrane, with the soft palate by the glossopalatine arches, and with the throat by the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle and the mucous membrane. It also forms the anterior wall of the oropharynx.

The boilerplate length of the human tongue from the oropharynx to the tip is x cm.[4] The boilerplate weight of the homo tongue from developed males is 70g and for adult females 60g.[ citation needed ]

In phonetics and phonology, a distinction is made between the tip of the tongue and the blade (the portion just behind the tip). Sounds made with the tongue tip are said to be upmost, while those fabricated with the tongue bract are said to be laminal.

Upper surface of the tongue [edit]

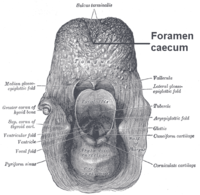

Foramen cecum and terminal sulcus labelled above

Features of the tongue surface

The upper surface of the tongue is chosen the dorsum, and is divided past a groove into symmetrical halves by the median sulcus. The foramen cecum marks the cease of this division (at about 2.5 cm from the root of the tongue) and the beginning of the terminal sulcus. The foramen cecum is also the point of attachment of the thyroglossal duct and is formed during the descent of the thyroid diverticulum in embryonic development.

The terminal sulcus is a shallow groove that runs forward as a shallow groove in a Five shape from the foramen cecum, forrard and outwards to the margins (borders) of the tongue. The terminal sulcus divides the tongue into a posterior pharyngeal part and an anterior oral office. The pharyngeal part is supplied by the glossopharyngeal nerve and the oral part is supplied by the lingual nerve (a branch of the mandibular branch (V3) of the trigeminal nerve) for somatosensory perception and by the chorda tympani (a co-operative of the facial nervus) for gustatory modality perception.

Both parts of the tongue develop from dissimilar pharyngeal arches.

Undersurface of the tongue [edit]

On the undersurface of the tongue is a fold of mucous membrane called the frenulum that tethers the tongue at the midline to the flooring of the oral fissure. On either side of the frenulum are small prominences called sublingual caruncles that the major salivary submandibular glands drain into.

Muscles [edit]

The eight muscles of the human tongue are classified equally either intrinsic or extrinsic. The four intrinsic muscles act to alter the shape of the tongue, and are not attached to any os. The four extrinsic muscles deed to modify the position of the tongue, and are anchored to bone.

Extrinsic [edit]

Lateral view of the natural language, with extrinsic muscles highlighted

The four extrinsic muscles originate from bone and extend to the natural language. They are the genioglossus, the hyoglossus (often including the chondroglossus) the styloglossus, and the palatoglossus. Their main functions are altering the tongue'southward position allowing for protrusion, retraction, and side-to-side movement.[5]

The genioglossus arises from the mandible and protrudes the tongue. It is also known as the tongue's "safety muscle" since it is the but muscle that propels the natural language frontward.

The hyoglossus, arises from the hyoid bone and retracts and depresses the tongue. The chondroglossus is often included with this musculus.

The styloglossus arises from the styloid procedure of the temporal os and draws the sides of the natural language upwards to create a trough for swallowing.

The palatoglossus arises from the palatine aponeurosis, and depresses the soft palate, moves the palatoglossal fold towards the midline, and elevates the back of the tongue during swallowing.

Intrinsic [edit]

Coronal section of tongue, showing intrinsic muscles

Four paired intrinsic muscles of the tongue originate and insert within the natural language, running along its length. They are the superior longitudinal muscle, the inferior longitudinal muscle, the vertical muscle, and the transverse muscle. These muscles alter the shape of the tongue by lengthening and shortening it, curling and uncurling its apex and edges as in tongue rolling, and flattening and rounding its surface. This provides shape and helps facilitate speech, swallowing, and eating.[5]

The superior longitudinal muscle runs along the upper surface of the tongue nether the mucous membrane, and elevates, assists in retraction of, or deviates the tip of the tongue. It originates well-nigh the epiglottis, at the hyoid os, from the median fibrous septum.

The inferior longitudinal musculus lines the sides of the natural language, and is joined to the styloglossus muscle.

The vertical muscle is located in the middle of the tongue, and joins the superior and inferior longitudinal muscles.

The transverse muscle divides the tongue at the heart, and is attached to the mucous membranes that run along the sides.

Blood supply [edit]

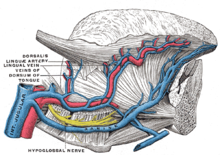

Blood supply of the natural language

The tongue receives its claret supply primarily from the lingual artery, a branch of the external carotid avenue. The lingual veins drain into the internal jugular vein. The flooring of the oral fissure also receives its blood supply from the lingual artery.[5] There is also a secondary blood supply to the root of natural language from the tonsillar branch of the facial artery and the ascending pharyngeal artery.

An area in the neck sometimes called the Pirogov triangle is formed by the intermediate tendon of the digastric muscle, the posterior border of the mylohyoid muscle, and the hypoglossal nerve.[6] [seven] The lingual artery is a good place to stop severe hemorrhage from the natural language.

Nerve supply [edit]

Innervation of the tongue consists of motor fibers, special sensory fibers for taste, and full general sensory fibers for awareness.[5]

- Motor supply for all intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the natural language is supplied past efferent motor nerve fibers from the hypoglossal nerve (CN XII), with the exception of the palatoglossus, which is innervated by the vagus nerve (CN 10).[5]

Innervation of taste and sensation is different for the inductive and posterior role of the tongue because they are derived from unlike embryological structures (pharyngeal curvation one and pharyngeal arches 3 and iv, respectively).[eight]

- Anterior ii-thirds of tongue (anterior to the vallate papillae):

- Taste: chorda tympani branch of the facial nerve (CN VII) via special visceral afferent fibers

- Sensation: lingual branch of the mandibular (V3) division of the trigeminal nerve (CN Five) via general visceral afferent fibers

- Posterior one third of natural language:

- Sense of taste and sensation: glossopharyngeal nervus (CN 9) via a mixture of special and general visceral afferent fibers

- Base of tongue

- Sense of taste and sensation: internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve (itself a branch of the vagus nerve, CN X)

Lymphatic drainage [edit]

The tip of tongue drains to the submental nodes. The left and right halves of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue drains to submandibular lymph nodes, while the posterior ane-tertiary of the natural language drains to the jugulo-omohyoid nodes.

Microanatomy [edit]

Department through the human tongue; stained H&E

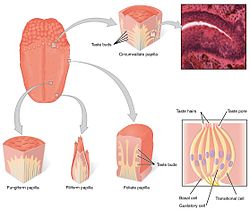

The upper surface of the tongue is covered in masticatory mucosa, a type of oral mucosa which is of keratinized stratified squamous epithelium. Embedded in this are numerous papillae, some of which house the taste buds and their taste receptors.[9] The lingual papillae consist of filiform, fungiform, vallate and foliate papillae,[5] and but the filiform papillae are not associated with any taste buds.

The tongue can divide itself in dorsal and ventral surface. The dorsal surface is a stratified squamous keratinized epithelium which is characterized by numerous mucosal projections called papillae.[10] The lingual papillae covers the dorsal side of the tongue towards the front of the terminal groove. The ventral surface is stratified squamous non-keratinized epithelium which is smooth.[xi]

Development [edit]

Floor of pharynx at well-nigh 26 days showing lateral swellings at offset pharyngeal arch (mandibular arch).

The tongue begins to develop in the fourth week of embryonic development from a median swelling – the median natural language bud (tuberculum impar) of the showtime pharyngeal arch.[12]

In the fifth week a pair of lateral lingual swellings, one on the right side and 1 on the left, grade on the first pharyngeal arch. These lingual swellings quickly aggrandize and cover the median tongue bud. They grade the anterior part of the natural language that makes up 2-thirds of the length of the tongue, and continue to develop through prenatal development. The line of their fusion is marked by the median sulcus.[12]

In the fourth calendar week a swelling appears from the 2d pharyngeal curvation, in the midline, chosen the copula. During the fifth and sixth weeks the copula is overgrown by a swelling from the third and quaternary arches (mainly from the tertiary arch) called the hypopharyngeal eminence, and this develops into the posterior role of the tongue (the other tertiary). The hypopharyngeal eminence develops mainly by the growth of endoderm from the tertiary pharyngeal arch. The boundary between the two parts of the tongue, the anterior from the first arch and the posterior from the third arch is marked by the terminal sulcus.[12] The concluding sulcus is shaped like a V with the tip of the V situated posteriorly. At the tip of the last sulcus is the foramen cecum, which is the betoken of zipper of the thyroglossal duct where the embryonic thyroid begins to descend.[5]

Role [edit]

Taste receptors are present on the human tongue in papillae

Taste [edit]

Chemicals that stimulate taste receptor cells are known as tastants. One time a tastant is dissolved in saliva, information technology tin brand contact with the plasma membrane of the gustatory hairs, which are the sites of gustatory modality transduction.[13]

The natural language is equipped with many taste buds on its dorsal surface, and each taste bud is equipped with taste receptor cells that can sense particular classes of tastes. Distinct types of gustatory modality receptor cells respectively detect substances that are sweet, bitter, salty, sour, spicy, or taste of umami.[14] Umami receptor cells are the least understood and accordingly are the type most intensively nether research.[15]

Mastication [edit]

The tongue is an important accessory organ in the digestive arrangement. The tongue is used for crushing nutrient confronting the difficult palate, during mastication and manipulation of food for softening prior to swallowing. The epithelium on the tongue's upper, or dorsal surface is keratinised. Consequently, the tongue can grind confronting the hard palate without beingness itself damaged or irritated.[16]

Speech [edit]

The intrinsic muscles of the tongue enable the shaping of the tongue which facilitates speech.

Intimacy [edit]

The tongue plays a role in physical intimacy and sexuality. The tongue is function of the erogenous zone of the mouth and can exist used in intimate contact, every bit in the French buss and in oral sex. The tongue tin be used for stimulating the clitoris and other areas of the vulva.

Clinical significance [edit]

Disease [edit]

A congenital disorder of the tongue is that of ankyloglossia also known every bit tongue-necktie. The tongue is tied to the flooring of the oral cavity by a very short and thickened frenulum and this affects speech, eating, and swallowing.

The natural language is decumbent to several pathologies including glossitis and other inflammations such as geographic tongue, and median rhomboid glossitis; burning rima oris syndrome, oral hairy leukoplakia, oral candidiasis (thrush), black hairy tongue and fissured tongue.

There are several types of oral cancer that mainly impact the tongue. Generally these are squamous cell carcinomas.[17] [18]

Food debris, desquamated epithelial cells and bacteria oftentimes grade a visible natural language coating.[19] This coating has been identified as a major factor contributing to bad breath (halitosis),[nineteen] which tin be managed past using a tongue cleaner.[20]

Medication delivery [edit]

The sublingual region underneath the front of the tongue is an platonic location for the administration of sure medications into the trunk. The oral mucosa is very thin underneath the tongue, and is underlain past a plexus of veins. The sublingual road takes advantage of the highly vascular quality of the oral crenel, and allows for the speedy application of medication into the cardiovascular system, bypassing the gastrointestinal tract. This is the simply convenient and efficacious road of administration (apart from Intravenous therapy) of nitroglycerin to a patient suffering chest hurting from angina pectoris.

Other animals [edit]

The muscles of the tongue evolved in amphibians from occipital somites. Most amphibians show a proper tongue afterwards their metamorphosis.[21] As a consequence virtually vertebrate animals—amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals—accept tongues (the frog family unit of pipids lack tongue). In mammals such as dogs and cats, the tongue is often used to make clean the fur and body by licking. The tongues of these species have a very rough texture which allows them to remove oils and parasites. Some dogs accept a tendency to consistently lick a office of their foreleg which tin can effect in a skin condition known as a lick granuloma. A dog's tongue as well acts equally a heat regulator. Every bit a dog increases its practise the natural language volition increase in size due to greater blood flow. The tongue hangs out of the domestic dog'south oral fissure and the moisture on the tongue volition piece of work to cool the bloodflow.[22] [23]

Some animals have tongues that are specially adapted for communicable prey. For example, chameleons, frogs, pangolins and anteaters have prehensile tongues.

Other animals may have organs that are analogous to tongues, such as a butterfly'due south proboscis or a radula on a mollusc, merely these are not homologous with the tongues found in vertebrates and ofttimes have little resemblance in office. For instance, butterflies practise not lick with their proboscides; they suck through them, and the proboscis is not a unmarried organ, but two jaws held together to form a tube.[24] Many species of fish have minor folds at the base of their mouths that might informally exist called tongues, just they lack a muscular structure like the true tongues plant in about tetrapods.[25] [26]

Society and culture [edit]

Figures of spoken language [edit]

The tongue tin can exist used as a metonym for language. For example, the New Testament of the Bible, in the Book of Acts of the Apostles, Jesus' disciples on the Day of Pentecost received a type of spiritual souvenir: "there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues ....", which amazed the oversupply of Jewish people in Jerusalem, who were from various parts of the Roman Empire but could now sympathize what was being preached. The phrase mother tongue is used equally a child's first language. Many languages[27] take the aforementioned give-and-take for "tongue" and "language".

A common temporary failure in word retrieval from memory is referred to equally the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. The expression tongue in cheek refers to a statement that is not to be taken entirely seriously – something said or washed with subtle ironic or sarcastic humor. A tongue twister is a phrase fabricated specifically to be very hard to pronounce. Aside from existence a medical status, "tongue-tied" means being unable to say what you want due to defoliation or restriction. The phrase "true cat got your tongue" refers to when a person is speechless. To "bite one's tongue" is a phrase which describes holding dorsum an opinion to avoid causing offence. A "sideslip of the tongue" refers to an unintentional utterance, such as a Freudian slip. The "gift of tongues" refers to when one is uncommonly gifted to exist able to speak in a strange language, often every bit a type of spiritual gift. Speaking in tongues is a common phrase used to describe glossolalia, which is to brand smoothen, language-resembling sounds that is no true speech communication itself. A deceptive person is said to have a forked tongue, and a smooth-talking person said to accept a argent tongue.

Gestures [edit]

Sticking 1'southward tongue out at someone is considered a childish gesture of rudeness or defiance in many countries; the act may too have sexual connotations, depending on the fashion in which it is washed. However, in Tibet information technology is considered a greeting.[28] In 2009, a farmer from Fabriano, Italia, was convicted and fined by the country's highest courtroom for sticking his tongue out at a neighbor with whom he had been arguing. Proof of the affront had been captured with a cell phone camera.[29]

Torso fine art [edit]

Natural language piercing and splitting have become more mutual in western countries in recent decades. In 1 study, one-5th of young adults were establish to have at least one type of oral piercing, nigh unremarkably the tongue.[30]

As food [edit]

The tongues of some animals are consumed and sometimes considered delicacies. Hot natural language sandwiches are frequently found on menus in kosher delicatessens in America. Taco de lengua (lengua being Spanish for tongue) is a taco filled with beef tongue, and is specially pop in Mexican cuisine. As role of Colombian gastronomy, Tongue in Sauce (Lengua en Salsa), is a dish prepared by frying the tongue, adding tomato sauce, onions and salt. Tongue can also be prepared as birria. Squealer and beef tongue are consumed in Chinese cuisine. Duck tongues are sometimes employed in Szechuan dishes, while lamb'southward tongue is occasionally employed in Continental and contemporary American cooking. Fried cod "natural language" is a relatively common part of fish meals in Norway and Newfoundland. In Argentine republic and Uruguay cow tongue is cooked and served in vinegar (lengua a la vinagreta). In the Czech Republic and Poland, a pork natural language is considered a effeminateness, and there are many means of preparing it. In Eastern Slavic countries, pork and beef tongues are usually consumed, boiled and garnished with horseradish or jelled; beef tongues fetch a significantly higher price and are considered more of a effeminateness. In Alaska, cow tongues are amid the more common.

Tongues of seals and whales accept been eaten, sometimes in large quantities, by sealers and whalers, and in diverse times and places have been sold for food on shore.[31]

Boosted images [edit]

-

The human tongue

-

Spots on the natural language

-

Exclusive Lines on the tongue

-

A cat displaying its comb-like tongue.

-

Medical analogy of a human mouth by Duncan Kenneth Winter

-

Distended canis familiaris tongue acting as a heat regulator

See also [edit]

- Electronic tongue

- Tongue map

- Song tract

References [edit]

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1125 of the 20th edition of Gray's Beefcake (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1125 of the 20th edition of Gray's Beefcake (1918)

- ^ hednk-024—Embryo Images at University of North Carolina

- ^ Maton, Anthea; Hopkins, Jean; McLaughlin, Charles William; Johnson, Susan; Warner, Maryanna Quon; LaHart, David; Wright, Jill D. (1993). Man Biological science and Health . Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN0-thirteen-981176-ane.

- ^ a b "Natural language". Online Etymology Dictionary . Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Kerrod, Robin (1997). MacMillan'southward Encyclopedia of Science. Vol. 6. Macmillan Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN0-02-864558-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M. (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Elsevier. pp. 989–995. ISBN978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ^ "Pirogov's triangle". Whonamedit? - A dictionary of medical eponyms. Ole Daniel Enersen.

- ^ Jamrozik, T.; Wender, West. (January 1952). "Topographic anatomy of lingual arterial anastomoses; Pirogov-Belclard'south triangle". Folia Morphologica. 3 (1): 51–62. PMID 13010300.

- ^ Dudek, Dr Ronald Due west. (2014). Board Review Series: Embryology (Sixth ed.). LWW. ISBN978-1451190380.

- ^ Bernays, Elizabeth; Chapman, Reginald. "taste bud | anatomy". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Fiore, Mariano; Eroschenko, Victor (2000). Di Fiore's atlas of histology with functional correlations (PDF). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 238.

- ^ Hib, José (2001). Histología de Di Fiore: texto y atlas . Buenos Aires: El Ateneo. p. 189. ISBN950-02-0386-3.

- ^ a b c Larsen, William J. (2001). Homo embryology (Tertiary ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Churchill Livingstone. pp. 372–374. ISBN0-443-06583-seven.

- ^ Tortora, Gerard J.; Derrickson, Bryan H. (2008). "17". Principles of Beefcake and Physiology (12th ed.). Wiley. p. 602. ISBN978-0470084717.

- ^ Silverhorn, Dee Unglaub (2009). "x". Human Physiology: An integrated arroyo (5th ed.). Benjamin Cummings. p. 352. ISBN978-0321559807.

- ^ Schacter, Daniel L.; Gilbert, Daniel Todd; Wegner, Daniel M. (2009). "Sensation and Perception". Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Worth. p. 166. ISBN9780716752158.

- ^ Atkinson, Martin E. (2013). Beefcake for Dental Students (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0199234462.

the natural language is also responsible for the shaping of the bolus as food passes from the rima oris to the rest of the alimentary canal

- ^ "Oral Cancer Facts". The Oral Cancer Foundation. 28 August 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Lam, L.; Logan, R. M.; Luke, C. (March 2006). "Epidemiological assay of natural language cancer in South Australia for the 24-yr flow, 1977-2001" (PDF). Australian Dental Journal. 51 (ane): 16–22. doi:10.1111/j.1834-7819.2006.tb00395.x. hdl:2440/22632. PMID 16669472.

- ^ a b Newman, Michael G.; Takei, Henry; Klokkevold, Perry R.; Carranza, Fermin A. (2012). Carranza'due south Clinical Periodontology (11th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 84–96. ISBN978-1-4377-0416-vii.

- ^ Outhouse, TL; Al-Alawi, R; Fedorowicz, Z; Keenan, JV (April 19, 2006). Outhouse, Trent L (ed.). "Tongue scraping for treating halitosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005519. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005519.pub2. PMID 16625641. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005519.pub3)

- ^ Iwasaki, Shin-ichi (July 2002). "Evolution of the structure and role of the vertebrate tongue". Journal of Anatomy. 201 (ane): 1–thirteen. doi:x.1046/j.1469-7580.2002.00073.10. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC1570891. PMID 12171472.

- ^ "A Domestic dog'southward Natural language". DrDog.com. Dr. Dog Brute Health Care Partitioning of BioChemics. 2014.

- ^ Krönert, H.; Pleschka, K. (Jan 1976). "Lingual blood flow and its hypothalamic control in the dog during panting". Pflügers Archiv: European Journal of Physiology. 367 (i): 25–31. doi:x.1007/BF00583652. ISSN 0031-6768. PMID 1034283. S2CID 23295086.

- ^ Richards, O. W.; Davies, R. G. (1977). Imms' General Textbook of Entomology: Volume 1: Structure, Physiology and Development, Volume 2: Nomenclature and Biology. Berlin: Springer. ISBN0-412-61390-five.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas Southward. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, Philadelphia: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 298–299. ISBN0-03-910284-Ten.

- ^ Kingsley, John Sterling (1912). Comparative anatomy of vertebrates. P. Blackiston'south Son & Co. pp. 217–220. ISBN1-112-23645-seven.

- ^ Afrikaans tong; Danish tunge; Albanian gjuha; Armenian lezu (լեզու); Greek glóssa (γλώσσα); Irish teanga; Manx çhengey; Latin and Italian lingua; Catalan llengua; French langue; Portuguese língua; Spanish lengua; Romanaian limba; Bulgarian ezik (език); Polish język; Russian yazyk (язык); Czech and Slovak jazyk; Slovene, Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian jezik; Kurdish ziman (زمان); Western farsi and Urdu zabān (زبان); Standard arabic lisān (لسان); Aramaic liššānā (ܠܫܢܐ/לשנא); Hebrew lāšon (לָשׁוֹן); Maltese ilsien; Estonian keel; Finnish kieli; Hungarian nyelv; Azeri and Turkish dil; Kazakh and Khakas til (тіл)

- ^ Bhuchung One thousand Tsering (27 December 2007). "Tibetan culture in the 21st century". Retrieved 13 Feb 2012.

- ^ United Press International (19 Dec 2009). "Sticking out your tongue ruled illegal". Rome, Italy. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Liran, Levin; Yehuda, Zadik; Tal, Becker (December 2005). "Oral and dental complications of intra-oral piercing". Paring Traumatol. 21 (6): 341–3. doi:10.1111/j.1600-9657.2005.00395.ten. PMID 16262620.

- ^ Hawes, Charles Boardman (1924). Whaling. Doubleday.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tongues. |

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to: Natural language |

| | Look up tongue in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Academy of Manitoba, Beefcake of the Vocal Tract

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tongue

0 Response to "What Does Under a Babys Tounge Look Like"

Post a Comment