What Does a Baby Monarch Caterpillar Look Like Milk Weed Tussock Moth Looks Like

Caterpillars ( KAT-ər-pil-ər) are the larval phase of members of the order Lepidoptera (the insect order comprising butterflies and moths).

As with most common names, the application of the give-and-take is arbitrary, since the larvae of sawflies (suborder Symphyta) are commonly called caterpillars every bit well.[1] [2] Both lepidopteran and symphytan larvae have eruciform trunk shapes.

Caterpillars of most species eat institute material (oftentimes leaves), simply not all; some (most 1%) eat insects, and some are even cannibalistic. Some feed on other animal products. For example, clothes moths feed on wool, and horn moths feed on the hooves and horns of dead ungulates.

Caterpillars are typically voracious feeders and many of them are among the most serious of agronomical pests. In fact, many moth species are best known in their caterpillar stages because of the harm they cause to fruits and other agricultural produce, whereas the moths are obscure and exercise no direct harm. Conversely, various species of caterpillar are valued as sources of silk, every bit human or fauna food, or for biological control of pest plants.

Etymology

The origins of the word "caterpillar" date from the early 16th century. They derive from Middle English catirpel, catirpeller, probably an alteration of Quondam North French catepelose: cate, true cat (from Latin cattus) + pelose, hairy (from Latin pilōsus).[3]

The inchworm, or looper caterpillars from the family Geometridae are then named because of the mode they move, appearing to measure the globe (the word geometrid means earth-measurer in Greek);[4] the chief reason for this unusual locomotion is the elimination of nearly all the prolegs except the clasper on the terminal segment.

Description

Crochets on a caterpillar's prolegs

Caterpillars take soft bodies that can abound rapidly betwixt moults. Their size varies between species and instars (moults) from as small as 1 millimetre (0.039 in) upwards to 14 centimetres (five.five in).[5] Some larvae of the guild Hymenoptera (ants, bees, and wasps) can appear like the caterpillars of the Lepidoptera. Such larvae are mainly seen in the sawfly suborder. However while these larvae superficially resemble caterpillars, they can exist distinguished past the presence of prolegs on every intestinal segment, an absence of crochets or hooks on the prolegs (these are present on lepidopteran caterpillars), one pair of prominent ocelli on the caput capsule, and an absence of the upside-downward Y-shaped suture on the front of the caput.[6]

Lepidopteran caterpillars can exist differentiated from sawfly larvae past:

- the numbers of pairs of pro-legs; sawfly larvae have 6 or more pairs while caterpillars have a maximum of 5 pairs.

- the number of stemmata (elementary eyes); the sawfly larvae have only two,[7] while caterpillars usually accept twelve (six each side of the head).

- the presence of crochets on the prolegs; these are absent-minded in the sawflies.

- sawfly larvae have an invariably smooth head capsule with no cleavage lines, while lepidopterous caterpillars carry an inverted "Y" or "Five" (adfrontal suture).

Fossils

In 2019, a geometrid moth caterpillar dating back to the Eocene epoch, approximately 44 million years ago, was establish preserved in Baltic bister. It was described nether Eogeometer vadens.[8] [9] [10] Previously, another fossil dating dorsum approximately 125 million years was plant in Lebanese amber.[eleven] [12]

Defenses

Many animals feed on caterpillars as they are rich in protein. As a result, caterpillars take evolved various means of defence.

Caterpillars take evolved defenses against concrete conditions such as cold, hot or dry out ecology conditions. Some Arctic species similar Gynaephora groenlandica have special basking and aggregation behaviours[13] apart from physiological adaptations to remain in a dormant state.[14]

Appearance

Costa Rican hairy caterpillar. The spiny beard are a cocky-defense mechanism

The appearance of a caterpillar can frequently repel a predator: its markings and sure body parts can make information technology seem poisonous, or bigger in size and thus threatening, or non-edible. Some types of caterpillars are indeed poisonous or distasteful and their bright coloring warns predators of this. Others may mimic unsafe caterpillars or other animals while not existence dangerous themselves. Many caterpillars are cryptically colored and resemble the plants on which they feed. An example of caterpillars that use cover-up for defense is the species Nemoria arizonaria. If the caterpillars hatch in the spring and feed on oak catkins they appear green. If they hatch in the summer they announced dark colored, like oak twigs. The differential development is linked to the tannin content in the nutrition.[15] Caterpillars may even have spines or growths that resemble establish parts such as thorns. Some look like objects in the surround such equally bird droppings. Some Geometridae cover themselves in plant parts, while bagworms construct and alive in a handbag covered in sand, pebbles or plant material.

Chemic defenses

More aggressive self-defense force measures are taken past some caterpillars. These measures include having spiny bristles or long fine hair-like setae with detachable tips that volition irritate by lodging in the peel or mucous membranes.[vi] However some birds (such as cuckoos) will swallow fifty-fifty the hairiest of caterpillars. Other caterpillars acquire toxins from their host plants that render them unpalatable to almost of their predators. For case, ornate moth caterpillars utilize pyrrolizidine alkaloids that they obtain from their food plants to deter predators.[16] The most aggressive caterpillar defenses are bristles associated with venom glands. These bristles are called urticating hairs. A venom which is among the nearly strong defensive chemicals in any animal is produced by the Due south American silk moth genus Lonomia. Its venom is an anticoagulant powerful enough to cause a human to hemorrhage to decease (Come across Lonomiasis).[17] This chemical is being investigated for potential medical applications. Most urticating hairs range in effect from mild irritation to dermatitis. Example: brown-tail moth.

Plants contain toxins which protect them from herbivores, but some caterpillars have evolved countermeasures which enable them to eat the leaves of such toxic plants. In add-on to being unaffected by the poison, the caterpillars sequester it in their body, making them highly toxic to predators. The chemicals are likewise carried on into the adult stages. These toxic species, such as the cinnabar moth (Tyria jacobaeae) and monarch (Danaus plexippus) caterpillars, usually annunciate themselves with the danger colors of blood-red, yellow and black, oft in bright stripes (see aposematism). Whatsoever predator that attempts to swallow a caterpillar with an ambitious defense mechanism will acquire and avert future attempts.

Some caterpillars regurgitate acidic digestive juices at attacking enemies. Many papilionid larvae produce bad smells from extrudable glands called osmeteria.

Defensive behaviors

Caterpillars linked together into a "procession"

Many caterpillars display feeding behaviors which allow the caterpillar to remain hidden from potential predators. Many feed in protected environments, such every bit enclosed inside silk galleries, rolled leaves or by mining between the leaf surfaces.

Some caterpillars, similar early instars of the lycopersicon esculentum hornworm and tobacco hornworm, accept long "whip-similar" organs attached to the ends of their body. The caterpillar wiggles these organs to frighten abroad flies and predatory wasps.[18] Some caterpillars can evade predators by using a silk line and dropping off from branches when disturbed. Many species thrash near violently when disturbed to scare away potential predators. 1 species (Amorpha juglandis) fifty-fifty makes loftier pitched whistles that tin scare away birds.[19]

Social behaviors and relationships with other insects

Some caterpillars obtain protection by associating themselves with ants. The Lycaenid butterflies are especially well known for this. They communicate with their ant protectors by vibrations likewise equally chemical ways and typically provide nutrient rewards.[20]

Some caterpillars are gregarious; large aggregations are believed to help in reducing the levels of parasitization and predation.[21] Clusters amplify the point of aposematic coloration, and individuals may participate in group regurgitation or displays. Pine processionary (Thaumetopoea pityocampa) caterpillars often link into a long train to movement through trees and over the basis. The head of the lead caterpillar is visible, only the other heads can appear hidden.[22] Woods tent caterpillars cluster during periods of common cold weather.

Predators

Caterpillars are eaten by many animals. The European pied flycatcher is one species that preys upon caterpillars. The flycatcher typically finds caterpillars among oak foliage. Paper wasps, including those in the genus Polistes and Polybia catch caterpillars to feed their young and themselves.

Beliefs

Caterpillars have been called "eating machines", and eat leaves voraciously. Almost species shed their skin four or v times as their bodies grow, and they eventually enter a pupal stage before becoming adults.[23] Caterpillars grow very apace; for instance, a tobacco hornworm will increment its weight ten-thousandfold in less than xx days. An accommodation that enables them to eat so much is a machinery in a specialized midgut that quickly transports ions to the lumen (midgut cavity), to go along the potassium level college in the midgut cavity than in the hemolymph.[24]

Virtually caterpillars are solely herbivorous. Many are restricted to feeding on one species of institute, while others are polyphagous. Some, including the clothes moth, feed on detritus. Some are predatory, and may prey on other species of caterpillars (eastward.k. Hawaiian Eupithecia). Others feed on eggs of other insects, aphids, scale insects, or ant larvae. A few are parasitic on cicadas or foliage hoppers (Epipyropidae).[25] Some Hawaiian caterpillars (Hyposmocoma molluscivora) use silk traps to capture snails.[26]

Many caterpillars are nocturnal. For case, the "cutworms" (of the family unit Noctuidae) hide at the base of plants during the 24-hour interval and only feed at night.[27] Others, such as gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar) larvae, modify their activity patterns depending on density and larval stage, with more than diurnal feeding in early on instars and high densities.[28]

Economic furnishings

Caterpillars crusade much damage, mainly past eating leaves. The propensity for damage is enhanced past monocultural farming practices, peculiarly where the caterpillar is specifically adapted to the host plant under tillage. The cotton bollworm causes enormous losses. Other species eat nutrient crops. Caterpillars have been the target of pest control through the use of pesticides, biological command and agronomic practices. Many species have become resistant to pesticides. Bacterial toxins such as those from Bacillus thuringiensis which are evolved to affect the gut of Lepidoptera have been used in sprays of bacterial spores, toxin extracts and also by incorporating genes to produce them within the host plants. These approaches are defeated over time by the evolution of resistance mechanisms in the insects.[29]

Plants evolve mechanisms of resistance to being eaten by caterpillars, including the development of chemical toxins and concrete barriers such as hairs. Incorporating host establish resistance (HPR) through found convenance is another approach used in reducing the impact of caterpillars on crop plants.[xxx]

Some caterpillars are used in industry. The silk industry is based on the silkworm caterpillar.

Human health

Cadet moth caterpillar sting on a shin twenty-4 hours later occurrence in due south Louisiana. The reddish mark covers an area about 20 mm (0.79 in) at its widest point past most 70 mm (2.8 in) in length.

Caterpillar pilus can be a cause of human wellness problems. Caterpillar hairs sometimes take venoms in them and species from approximately 12 families of moths or butterflies worldwide can inflict serious human being injuries ranging from urticarial dermatitis and atopic asthma to osteochondritis, consumption coagulopathy, kidney failure, and brain bleeding.[31] Skin rashes are the most common, simply there have been fatalities.[32] Lonomia is a frequent crusade of envenomation in Brazil, with 354 cases reported between 1989 and 2005. Lethality ranging up to 20% with expiry acquired most often past intracranial hemorrhage.[33]

Caterpillar hair has as well been known to cause kerato-conjunctivitis. The precipitous barbs on the end of caterpillar hairs can go lodged in soft tissues and mucous membranes such as the eyes. Once they enter such tissues, they tin be difficult to extract, often exacerbating the problem every bit they migrate across the membrane.[34]

This becomes a particular problem in an indoor setting. The hair hands enter buildings through ventilation systems and accrue in indoor environments because of their small size, which makes it difficult for them to be vented out. This accumulation increases the risk of human contact in indoor environments.[35]

Caterpillars are a food source in some cultures. For instance, in S Africa mopane worms are eaten by the bushmen, and in China silkworms are considered a delicacy.

In popular civilisation

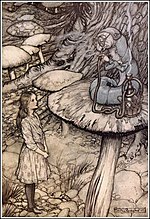

William Blake's analogy of a caterpillar overlooking a kid from his illustrated book For Children The Gates of Paradise.[36]

In the Onetime Testament of the Bible caterpillars are feared as pest that devour crops. They are function of the "pestilence, blasting, mildew, locust"[37] considering of their association with the locust, thus they are one of the plagues of Egypt. Jeremiah names them as one of the inhabitants of Babylon. The English word caterpillar derives from the erstwhile French catepelose (hairy cat) but merged with the piller (pillager). Caterpillars became a symbol for social dependents. Shakespeare's Bolingbroke described King Richard'south friends as "The caterpillars of the republic, Which I take sworn to weed and pluck away". In 1790 William Blake referenced this popular image in The Union of Heaven and Hell when he attacked priests: "as the caterpillar chooses the fairest leaves to lay her eggs on, and so the priest lay his curse on the fairest joys".[38]

The role of caterpillars in the life stages of collywobbles was badly understood. In 1679 Maria Sibylla Merian published the showtime book of The Caterpillars' Marvelous Transformation and Strange Floral Food, which independent 50 illustrations and a clarification of insects, moths, butterflies and their larvae.[39] An earlier popular publication on moths and butterflies, and their caterpillars, by January Goedart had not included eggs in the life stages of European moths and butterflies, because he had believed that caterpillars were generated from water. When Merian published her study of caterpillars it was still widely believed that insects were spontaneously generated. Merian's illustrations supported the findings of Francesco Redi, Marcello Malpighi and Jan Swammerdam.[forty]

Butterflies were regarded every bit symbol for the human soul since ancient time, and also in the Christian tradition.[41] Goedart thus located his empirical observations on the transformation of caterpillars into butterflies in the Christian tradition. Equally such he argued that the metamorphosis from caterpillar into butterfly was a symbol, and even proof, of Christ's resurrection. He argued "that from expressionless caterpillars sally living animals; so it is as truthful and miraculous, that our dead and rotten corpses volition ascent from the grave."[42] Swammerdam, who in 1669 had demonstrated that inside a caterpillar the rudiments of the futurity butterfly's limbs and wings could be discerned, attacked the mystical and religious notion that the caterpillar died and the butterfly later resurrected.[43] As a militant Cartesian, Swammerdam attacked Goedart equally ridiculous, and when publishing his findings he proclaimed "here we witness the digression of those who have tried to prove Resurrection of the Dead from these obviously natural and comprehensible changes within the fauna itself."[44]

Since then the metamorphoses of the caterpillar into a butterfly has in Western societies been associated with countless human transformations in folktales and literature. There is no process in the concrete life of human beings that resembles this metamorphoses, and the symbol of the caterpillar tends to depict a psychic transformation of a human. Every bit such the caterpillar has in the Christian tradition go a metaphor for being "born again".[45]

Famously, in Lewis Carroll'south Alice'south Adventures in Wonderland a caterpillar asks Alice "Who are you?". When Alice comments on the caterpillar'southward inevitable transformation into a butterfly, the caterpillar champions the position that in spite of changes it is notwithstanding possible to know something, and that Alice is the aforementioned Alice at the starting time and finish of a considerable interval.[46] When the Caterpillar asks Alice to clarify a signal, the child replies "I'm agape I tin can't put it more conspicuously... for I can't just sympathize information technology myself, to begin with, and being then many different sizes in a 24-hour interval is very confusing". Here Carroll satirizes René Descartes, the founder of Cartesian philosophy, and his theory on innate ideas. Descartes argued that nosotros are distracted by urgent bodily stimuli that swamp the human mind in childhood. Descartes as well theorised that inherited preconceived opinions obstruct the human perception of the truth.[47]

More than recent symbolic references to caterpillars in popular media include the Mad Men flavour 3 episode "The Fog", in which Betty Draper has a drug-induced dream, while in labor, that she captures a caterpillar and holds information technology firmly in her hand.[48] In The Sopranos season 5 episode "The Test Dream", Tony Soprano dreams that Ralph Cifaretto has a caterpillar on his bald head that changes into a butterfly.

Gallery

Click left or right for a slide show.

See likewise

- Edible caterpillars

- Larval food plants of Lepidoptera

- Lepidopterism - caterpillar dermatitis

- List of pests and diseases of roses

- Sericulture

References

- ^ Eleanor Anne Ormerod (1892). A Text-Book of Agronomical Entomology: Existence a Guide to Methods of Insect Life and Ways of Prevention of Insect Ravage for the Employ of Agriculturists and Agronomical Students. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Archived from the original on 2020-09-30. Retrieved 2016-01-27 .

- ^ Roger Fabian Anderson (January 1960). Forest and Shade Tree Entomology . Wiley. ISBN978-0-471-02739-3.

- ^ "Caterpillar" Archived 2011-09-09 at the Wayback Machine. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage Lexicon of the English language Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. (accessed: March 26, 2008).

- ^ "Geometridae." Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, n.d. Web. nineteen September 2017.

- ^ Hall, Donald Due west. (September 2014). "Featured Creatures: hickory horned devil, Citheronia regalis". University of Florida, Entomology and Nematology Department. Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ a b Scoble, MJ. 1995. The Lepidoptera: Form, Function and Diversity Archived 2013-12-31 at the Wayback Machine. Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-19-854952-0

- ^ Meyer-Rochow, Victor Benno (1974). "Construction and function of the larval center of the sawfly Perga". Periodical of Insect Physiology. 20 (viii): 1565–1591. doi:10.1016/0022-1910(74)90087-0. PMID 4854430.

- ^ a b Fischer, Thilo C.; Michalski, Artur; Hausmann, Axel (2019). "Geometrid caterpillar in Eocene Baltic amber (Lepidoptera, Geometridae)". Scientific Reports. 9 (one): Article number 17201. Bibcode:2019NatSR...917201F. doi:x.1038/s41598-019-53734-w. PMC6868187. PMID 31748672.

- ^ a b Muller, Natalie (20 November 2019). "German scientists find 44-million-year-onetime caterpillar". DW. Archived from the original on 21 November 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ a b Georgiou, Aristos (21 Nov 2019). "Scientists discover 'exceptional' 44-1000000-year-old caterpillar preserved in bister". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- ^ Grimaldi, David; Engel, Michael S. (June 2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-5218-2149-0. Archived from the original on 2018-ten-19. Retrieved 2019-11-24 .

- ^ Martill, David (13 January 2018). "Scientists take accidentally found the oldest e'er butterfly or moth fossils". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 24 Nov 2019.

- ^ Kukal, O.; B. Heinrich & J. G. Duman (1988). "Behavioral thermoregulation in the freeze-tolerant arctic caterpillar, Gynaeophora groenlandica". J. Exp. Biol. 138 (1): 181–193. doi:x.1242/jeb.138.i.181. Archived from the original on 2008-07-25. Retrieved 2010-06-26 .

- ^ Bennett, V. A.; Lee, R. Eastward.; Nauman, L. South.; Kukal, O. (2003). "Selection of overwintering microhabitats used by the arctic woollybear caterpillar, Gynaephora groenlandica" (PDF). Cryo Letters. 24 (3): 191–200. PMID 12908029. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2010-06-26 .

- ^ Greene, Due east (1989). "A Diet-Induced Developmental Polymorphism in a Caterpillar" (PDF). Science. 243 (4891): 643–646. Bibcode:1989Sci...243..643G. CiteSeerXten.i.1.462.1931. doi:ten.1126/science.243.4891.643. PMID 17834231. S2CID 23249256. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2017-10-27 .

- ^ Dussourd, D. E. (1988). "Biparental Defensive Endowment of Eggs with Acquired Plant Alkaloid in the Moth Utetheisa ornatrix". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 85 (16): 5992–996. Bibcode:1988PNAS...85.5992D. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.16.5992. PMC281891. PMID 3413071.

- ^ Malaque, Ceila Grand. S.; Lúcia Andrade; Geraldine Madalosso; Sandra Tomy; Flávio L. Tavares; Antonio C. Seguro (2006). "A case of hemolysis resulting from contact with a Lonomia caterpillar in southern Brazil". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 74 (v): 807–809. doi:ten.4269/ajtmh.2006.74.807. PMID 16687684.

- ^ Darby, Factor (1958). What is a Butterfly. Chicago: Benefic Printing. p. thirteen.

- ^ Bura, V. L.; Rohwer, V. G.; Martin, P. R.; Yack, J. E. (2010). "Whistling in caterpillars (Amorpha juglandis, Bombycoidea): Sound-producing mechanism and function". Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (Pt 1): xxx–37. doi:ten.1242/jeb.046805. PMID 21147966.

- ^ Lycaenid butterflies and ants Archived 2020-07-31 at the Wayback Machine. Australian museum (2009-10-14). Retrieved on 2012-08-14.

- ^ Entry, Grant L. Chiliad.; Lee A. Dyer. (2002). "On the Conditional Nature Of Neotropical Caterpillar Defenses against their Natural Enemies". Ecology. 83 (eleven): 3108–3119. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[3108:OTCNON]ii.0.CO;2. JSTOR 3071846. S2CID 14389136.

- ^ Terrence Fitzgerald. "Pine Processionary Caterpillar". Web.cortland.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-03-03. Retrieved 2013-05-08 .

- ^ Monarch Butterfly Archived 2013-08-25 at the Wayback Machine. Scienceprojectlab.com. Retrieved on 2012-08-14.

- ^ Chamberlin, M.E.; M.E. Rex (1998). "Changes in midgut active ion transport and metabolism during the 5th instar of the tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta)". J. Exp. Zool. 280 (2): 135–141. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19980201)280:2<135::AID-JEZ4>3.0.CO;2-P.

- ^ Pierce, N.E. (1995). "Predatory and parasitic Lepidoptera: Carnivores living on plants" (PDF). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 49 (4): 412–453. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-11-04 .

- ^ Rubinoff, Daniel; Haines, William P. (2005). "Web-spinning caterpillar stalks snails". Science. 309 (5734): 575. doi:10.1126/science.1110397. PMID 16040699. S2CID 42604851.

- ^ "Caterpillars of Pacific Northwest Forests and Woodlands". USGS. Archived from the original on 2009-05-08. Retrieved 2009-03-11 .

- ^ Lance, D. R.; Elkinton, J. Due south.; Schwalbe, C. P. (1987). "Behaviour of tardily-instar gypsy moth larvae in high and low density populations". Ecological Entomology. 12 (3): 267. doi:ten.1111/j.1365-2311.1987.tb01005.ten. S2CID 86040007. Archived from the original on 2020-10-19. Retrieved 2019-09-ten .

- ^ Tent Caterpillars and Gypsy Moths Archived 2013-09-10 at the Wayback Machine. Dec.ny.gov. Retrieved on 2012-08-14.

- ^ van Emden; H. F. (1999). "Transgenic Host Plant Resistance to Insects—Some Reservations". Register of the Entomological Society of America. 92 (6): 788–797. doi:ten.1093/aesa/92.half-dozen.788.

- ^ Diaz, HJ (2005). "The evolving global epidemiology, syndromic classification, management, and prevention of caterpillar envenoming". Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 72 (3): 347–357. doi:x.4269/ajtmh.2005.72.347. PMID 15772333.

- ^ Redd, JT; Voorhees, RE; Török, TJ (2007). "Outbreak of lepidopterism at a Boy Scout army camp". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 56 (6): 952–955. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.06.002. PMID 17368636.

- ^ Kowacs, PA; Cardoso, J; Entres, M; Novak, EM; Werneck, LC (December 2006). "Fatal intracerebral hemorrhage secondary to Lonomia obliqua caterpillar envenoming: case report". Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 64 (4): 1030–2. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2006000600029. PMID 17221019.

- ^ Patel RJ, Shanbhag RM (1973). "Ophthalmia nodosa – (a case report)". Indian J Ophthalmol. 21 (4): 208. Archived from the original on 2013-06-05. Retrieved 2010-06-26 .

- ^ Balit, C. R.; Ptolemy, H. C.; Geary, Chiliad. J.; Russell, R. C.; Isbister, Thou. One thousand. (2001). "Outbreak of caterpillar dermatitis caused by airborne hairs of the mistletoe browntail moth (Euproctis edwardsi)". The Medical Journal of Commonwealth of australia. 175 (11–12): 641–3. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143760.x. ISSN 0025-729X. PMID 11837874. S2CID 26910462. Archived from the original on 2011-04-04. Retrieved 2009-09-06 .

- ^ Morris Eaves; Robert North. Essick; Joseph Viscomi (eds.). "For Children: The Gates of Paradise, copy D, object one (Bentley 1, Erdman i, Keynes i) "For Children: The Gates of Paradise"". William Blake Archive. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ^ 1 Kings 8:37

- ^ Michael Ferber (2017). A Dictionary of Literary Symbols. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9781316780978.

- ^ Donna Spalding Andréolle; Veronique Molinari, eds. (2011). Women and Science, 17th Century to Present: Pioneers, Activists and Protagonists. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 36. ISBN9781443830676.

- ^ Donna Spalding Andréolle; Veronique Molinari, eds. (2011). Women and Science, 17th Century to Present: Pioneers, Activists and Protagonists. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 40. ISBN9781443830676.

- ^ Boria Sax (1998). The Serpent and the Swan: The Animal Bride in Folklore and Literature. Univ. of Tennessee Press. pp. 70. ISBN9780939923687.

- ^ Karl A. Eastward. Enenkel; Marker Due south. Smith (2007). Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature and the Visual Arts. BRILL. p. 157. ISBN9789047422365.

- ^ Karl A. E. Enenkel; Marking S. Smith (2007). Early Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature and the Visual Arts. BRILL. p. 161. ISBN9789047422365.

- ^ Karl A. Due east. Enenkel; Mark S. Smith (2007). Early on Modern Zoology: The Construction of Animals in Science, Literature and the Visual Arts. BRILL. p. 162. ISBN9789047422365.

- ^ Boria Sax (1998). The Serpent and the Swan: The Beast Helpmate in Sociology and Literature. Univ. of Tennessee Press. pp. 71. ISBN9780939923687.

- ^ Sherry Ackerman (2009). Backside the Looking Glass. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 103. ISBN9781443804561.

- ^ Sherry Ackerman (2009). Behind the Looking Drinking glass. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 99. ISBN9781443804561.

- ^ What's Alan Watching?: Mad Men, "The Fog"

External links

- Photos of caterpillars at Insecta.pro

- Images from 1837 calendar many images of catapillars

- Larva Locomotion: A Closer Look — video clips showing how monarch larvae walk

- More video clips from nature

- 3-D animation Papilio polyxenes larvae walking

- Britain moths.Life cycle images

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caterpillar

0 Response to "What Does a Baby Monarch Caterpillar Look Like Milk Weed Tussock Moth Looks Like"

Post a Comment